INFINITE WORLDS: A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE COMIC BOOK MULTIVERSE

Both DC Comics’ Multiversity series and Marvel Comics’ Edge of Spider-Verse event showcase characters from multiple parallel universes (that is, a “multiverse”). These two series are not the first time that the multiverse concept has been used by DC and Marvel. Over the years, the publishers have each established a multiverse of parallel universes in their respective comics, and the concept has become a popular element of superhero comics.

The concept of “parallel worlds” – defined by The Science Fiction Encyclopedia as “another universe situated ‘alongside’ our own, displaced from it along a spatial fourth dimension” – has a long history that predates science fiction. The parallel world concept can be found in ancient philosophy (for example, Platonism), religion, folklore, and myth (Heaven, Hell, and Asgard can be described as parallel worlds), and literature (Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass).

Stories featuring parallel worlds were popular in pulp science fiction magazines and the concept was also used in comic books. For example, in Captain Marvel Adventures#80 (1948), the comic’s titular superhero travels to a parallel world where a painter’s surrealist creations are real. More significantly, in Wonder Woman #59 (1953) Wonder Woman is transported to a parallel Earth when her lasso is struck by lightning. There, Wonder Woman encounters her twin, a superhero named Tara Terruna. For the first time, a superhero met another version of herself on a parallel world.

In 1956, DC Comics editor Julius Schwartz oversaw the revival of the comics character The Flash. First appearing in Flash Comics #1 (January 1940), the original Flash was Jay Garrick, who gains the power of super-speed after inhaling hard water vapors. The character’s adventures continued through the 1940s, the period labeled by comics historians as the “Golden Age of Comics”, and ended in 1951, when superhero comics lost their commercial appeal and were replaced by other genres like Westerns and horror comics.

Schwartz kept the superhero’s name and superpowers, but changed The Flash’s design and alter-ego. The Flash was now Barry Allen, a police scientist who gains super-speed when he is soaked in lightning-charged chemicals. The new Flash debuted in Showcase #4 (October 1956). Significantly, the comic acknowledges the original character’s existence; indeed, Barry Allen is inspired to assume his superhero identity because he reads the fictional comic book adventures of the Golden Age Flash.

The new Flash was commercially successful, reviving reader interest in superhero characters and comics; The Flash was the first superhero of the period comics historians label the “Silver Age of Comics”. At DC Comics, The Flash was soon joined by Silver Age superheroes The Atom, Hawkman, and Green Lantern; all of these heroes were based on past Golden Age superhero characters.

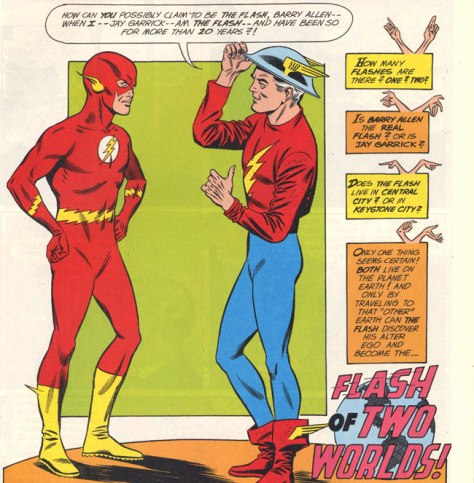

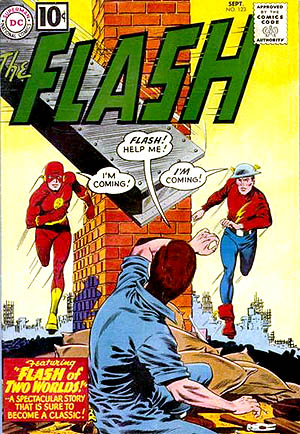

Comics fans were eager to see the return of the Golden Age Flash, and DC Comics obliged. The two Flash characters first met in The Flash #123 (September 1961) in the story “Flash of Two Worlds”, using the parallel world concept; the Silver Age Flash vibrates his molecules at a different frequency at super-speed and is accidentally transported to a parallel world, where the Golden Age Flash fought crime in the 1940s and is now retired.

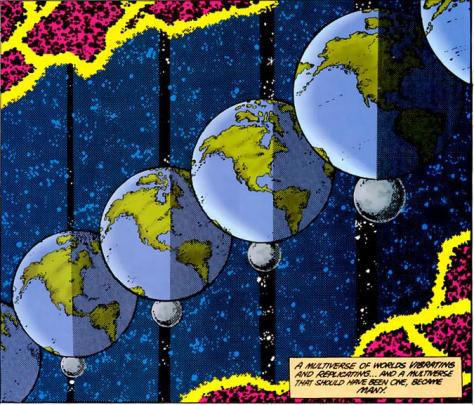

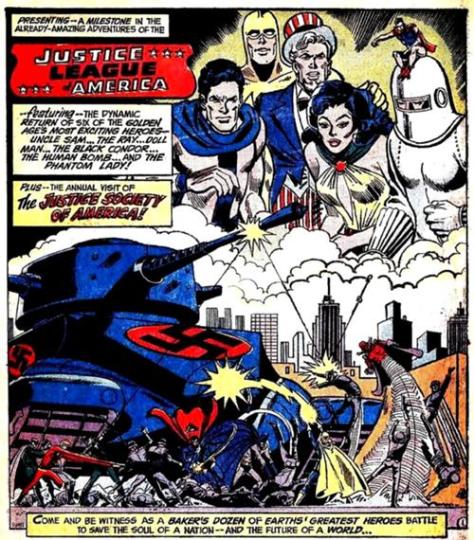

This parallel world (identified as “Earth-Two” in future stories) was the home of Golden Age characters like The Flash, The Spectre, and The Sandman, while Barry Allen’s world (“Earth-One”) was the home of the modern DC Comics superheroes. Soon, DC Comics added other parallel worlds, like Earth-Three (the home of supervillain versions of the Justice League of America), Earth-S (the home of Captain Marvel and other Fawcett Comics characters purchased by DC), and Earth-X (where the Quality Comics characters purchased by DC – Uncle Sam, Black Condor, etc. – fought the Nazis, who won World War II on that world). DC Comics soon had a robust fictional multiverse.

While DC Comics’ multiverse grew to include many parallel worlds, DC’s primary competitor, Marvel Comics, was slow to utilize the concept. Although Marvel featured stories with parallel worlds (such as the Negative Zone in Fantastic Four, Asgard in The Mighty Thor, or the dimension of the Squadron Supreme – superheroes based on DC Comics characters – in The Avengers ) it was not until 1983, when writer Alan Moore created the Captain Britain Corps in the pages of the Captain Britain strip, that a multiverse of parallel worlds – protected by the Captain Britain Corps – is identified. The strip’s titular hero is the Captain Britain of Marvel’s primary Earth, identified as Earth-616.

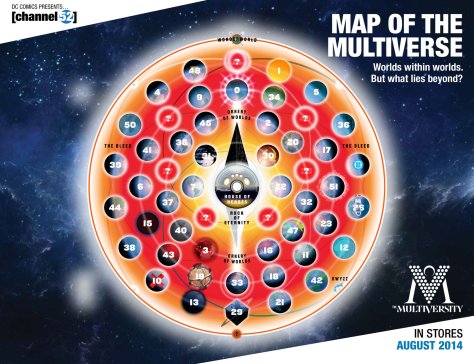

In 1985, DC Comics destroyed its multiverse in the crossover event Crisis on Infinite Earths, which revised DC’s narrative history so that there was now only one Earth; the Golden Age characters appeared in the 1940s and retired in the 1950s, but inspired the modern superheroes that came after them. However, DC Comics revived the multiverse concept in its weekly 52 comics series (2006) and the subsequent Flashpoint crossover event (2011), so that there are now 52 parallel Earths. These parallel Earths will be explored in the upcoming Multiversity series.

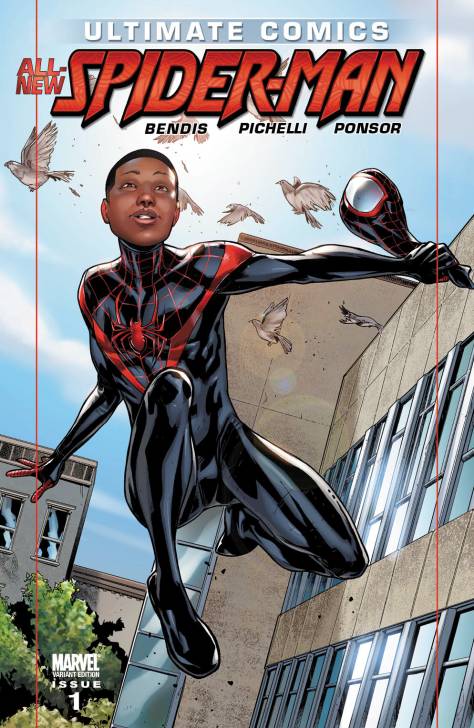

Marvel Comics’ multiverse continues to be well-utilized by creators. Earth-1610 (identified as the “Ultimate Universe”, the home of 21st century updates of the classic Marvel characters) has been the setting of several popular comics titles. Marvel’s upcoming Edge of Spider-Verse series will showcase versions of Spider-Man from across the Marvel multiverse.

The comic book multiverse is a narrative convention that allows for a huge range of fascinating stories, often featuring altered versions of familiar characters. Although some might argue that a comic book multiverse is confusing to new readers (as some DC Comics editors argued in the 1980s), the multiverse remains a popular concept among many comics fans.

The images above are the property of their respective owner(s), and are presented for educational purposes only under the fair use doctrine of the copyright laws of the United States of America.